In The Death and Life of Great American Cities Jane Jacobs is not concerned with how a city “ought” to look, she is concerned with how it works. The brunt of her argument is that cities have intricate and diverse uses that give each other mutual support economically and socially. Jacobs breaks up her book in four parts, with the first part focusing on ordinary scenes and events, the social behavior of people in cities. The second part is her argument that economic behavior of cities is the most important factor. Part three is about decay and regeneration, how cities are used, how cities and the people in them behave in real life. The fourth part is about the problems that cities create and suggests for changes in housing, traffic, design, planning, etc. Although Jacobs writes that the most important part of her argument is the economic and social behavior of cities, it is clear that one of the most important factors to Jacobs is REAL LIFE. Jacobs writes in her introduction that unsuccessful city areas that do not have the mutual support economically and socially and “ that the science of city planning and the art of city design, in real life for real cities, must become the science and art of catalyzing and nourishing these close-grained working relationships.” It is the lack of urban planners and anyone else involved in the development of great cities observing how real cities function well and how real life functions with the cities that Jacobs calls out. Jacobs uses a brief example of a housing project’s grass in New York and how everyone hated the grass who lived there because it was an illusion that all was well with the housing project when it really wasn’t. When developers built the place they never asked the people who were going to live there what they wanted, again the lack of dealing with real life.

Jacobs then goes on to list people who have had the greatest impact on city planning theory such as Ebenezer Howard, Sir Patrick Geddes, the Decentrists (Lewis Mumford, Clarence Stein, Henry Wright, and Catherine Bauer) and Le Corbusier. Howard’s did not like cities and his ideas for them according to Jacobs were city destroying. Howards Garden City model that was also embraced by the Decentrists, was to thin cities out, de-center them, create smaller separate cities or even towns. Streets were bad, people should never be on them, commerce and residence areas should always be separate from each other, and the city should be self-contained and never change or grow. Jacobs claims that the Decentrists only looked at the failing parts of a city and nothing else, which left them with no understanding as to how a successful city would look and work. Although the Decentrists were against Le Corbusier, he also adopted some of Howards’s Garden City ideas in his Radiant City, a “vertical garden city.”

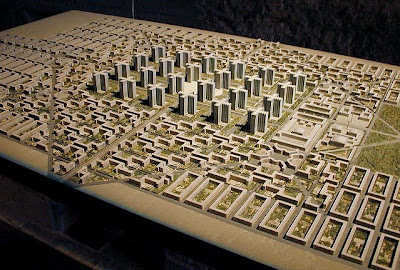

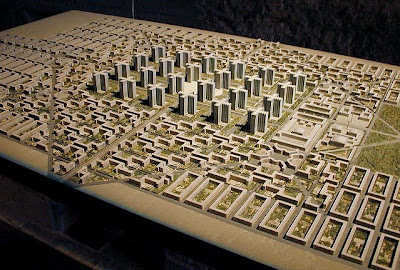

Le Corbusier’s vertical city was a city of towers with green all around and it embraced the unchangeable aspect of the Garden City plan. Le Corbusier felt that skyscrapers were the answer to the problems of cities. Many of these ideas became plans for low-income public housing. In many of the city of Chicago’s public housing developments, such as Cabrini Green, Robert Taylor Homes, Henry Horner Homes, and Harold Ickes Homes, the city embraced the high-rise building surrounded by green, and island off. All of these public housing plans have been deemed as failures that segregated low-income families off from the rest of the city, fostered gang activity, and created dangerous living environments. Today almost all are torn down and some are in the process of redevelopment in to smaller town homes with mixed income within the same space. The Garden City of the Decentrists and the Radiant City of Le Corbusier has had a great impact on the city of Chicago. Jacobs also claims that when she wrote the book in the 1950s city planners were combining the two plans to create cities and that this was a mistake.

In Jacobs’s chapter The Curse of Border Vacuums, she discusses how borders function in cities. Jacobs claims that massive single uses in cities create borders and those borders are damaging for neighborhoods in cities. Jacobs is concerned not with the social results of borders, but the physical and functional effects of borders on their direct surroundings. Things she lists as boarders are train tracks, waterfronts, big-city university campuses, civic centers, hospital grounds, and large parks. Since all of these types of boards she lists are not necessarily noisy unattractive, or undesirable of a location, there must be another reason that blight develops around these boards. Jacobs says that these boards form dead ends and walls for those who use city streets. She claims that for streets to stay safe there must be a constant mingling of people within these places for different reasons. The evidence Jacobs provides for this is an article published in the New York Post around the time she was writing the book, about a murder in an area that had become increasingly vacant once the construction of the Cross-Bronx Expressway began. Jacobs saw the construction of the Expressway creating lesson of a reason for people to go to that border causing fewer people to mingle in the area, causing shops to close early.

Jacobs divides all land in to two types general land and special land. General land is anywhere people circulate on foot in public, streets, small parks, and maybe building lobbies used like streets. Special land is not for public passage; people walk around it or next to it, it is technically in the way. A person circulating on foot in public is either not allowed in this special land or does not care to enter it, such as homes or places of work. Although special land contributes the people for general land, it also interferes with it. The evidence that Jacobs provides is a term used by downtown merchants “dead place” a place that goes empty on a downtown street. A dead place causes significant loss in foot traffic in the area around it because there is no use for it, and no reason for someone to go in to it or even go near it. This causes a “geographical obstacle to the general land.” Again, Jacobs shows when a border has only a single use than less people will come to it and mingle. Jacobs’s approach to correcting these single use borders is to create a seamless border. She suggests that parks should not put their activities such as ice-skating rinks in the center of the park but on the border. Then with corporation of the areas next to this border create something like a cafe or a place to rent skates in the area across from the border. This approach will allow for a seamless border that will help create multiple uses.

Robert Moses

In Robert Fishman’s Revolt of the Urbs the argument is that Moses’s critics of his plan to put a highway through Washington Square Park led to the larger debate on American Urbanism. One sees how Robert Moses convinced the public that he knew what was best for them, which was usually a massive clearing of any section of land that happened to be in his way for his great bridges, highways, expressways, and even parks. Moses forced relocation for numerous people who he saw as in the way of his projects. The battle to build a highway through New York’s Washington Square Park in the 1950s is where Moses met his greatest opposition, particularly that of Jane Jacobs. Moses wanted to build a highway through the park linking to his Lower Manhattan Expressway. This goes against everything Jacobs writes about in her chapter on boarders. According to Jacobs’s theory on borders, the highway would create more borders and fragment the park into single use pieces, which would diminish mingling of people in that area. The issues Jacobs and others bring up that were against Moses’s ideas were that diverse neighborhoods were at the heart of a city, pedestrians and mass transit should be focused on over the automobile, the importance of public space, and the “traditional streetscape” over skyscrapers in the park. Lastly, and probably the most important idea especially to Jacobs was listening to the people living in and using the city over the urban planner. This is where we come back to Jacobs’s argument that we need to observe “real life” to see how a city can function successfully, not just accepting the vision of the urban planner with the administrative power.

Extremely influenced by Le Corbusier’s ideas for the city of high towers with lots of room for automobiles on the ground, Moses embraced the automobile in the city. He rejected the small garden city town ideas of Mumford, but wanted to completely wipe out slum areas and rebuild a modern landscape. The House Act of 1949 not only secured government funding for many of Moses’s ideas, but also secured the support for clearing out the land he wanted to construct those ideas upon. It is clear that Moses’s unsuccessful attempt to fragment the park did not work, but he was responsible for many other projects that did just that through out the city of New York.

In Claes Oldenburg’s “The Street” and Urban Renewal in Greenwich Village, Joshua Shannon claims that Oldenburg relied on the “flames and wreckage” of New York’s Greenwich Village in the 1960s. He used this changing environment as his sort of canvas for his productions. The changing city was due to the modernist vision to create order within the city and to eliminate chaos. This meant getting rid of streets because that is where the chaos lies. The streets that photographer Helen Levitt photographed were the embodiment of this chaos with children using the streets as their playroom. In another of Oldenburg’s pieces, Snapshots of the City at the end of the performance he is hit by a cardboard car which is the final thing that finishes him off. This comment on the automobile is extremely appropriate for the time and the place. Oldenburg lived in the area around the Washington Square Park that had only just won its long battle of banning cars from the park.

Shannon points out the difference between Jane Jacobs’s view of the city and Oldenburg’s The Street was that Jacobs fought for a “delightfully quirky city” while The Street, portrayed it as dirty, violent, and full of poverty. The claim is that The Street’s image of the city is one of disorder or “of obdurate stuff refusing to be abstracted into order or legibility.” The point that Shannon is trying to make about Oldenburg’s work is that if he is trying to show an image of the city that is chaotic and disordered, he does not sell this image as a good one by depicting it as violent and dirty.

All of the readings this week discuss the ever-growing need by urban planners and city administrators to organize the chaos that in their eyes had taken over cities. Influenced from many different people from different countries what seems to be the biggest misconception by urban planners was their belief that one plan worked for all city problems and that this plan would be a permanent solution that would never need changing. This really leads me to agree with Jane Jacobs writing that there was a lack of observing real life in the city by urban planners and that without doing so they would never understand how a city could function well.

In The Death and Life of Great American Cities Jane Jacobs is not concerned with how a city “ought” to look, she is concerned with how it works. The brunt of her argument is that cities have intricate and diverse uses that give each other mutual support economically and socially. Jacobs breaks up her book in four parts, with the first part focusing on ordinary scenes and events, the social behavior of people in cities. The second part is her argument that economic behavior of cities is the most important factor. Part three is about decay and regeneration, how cities are used, how cities and the people in them behave in real life. The fourth part is about the problems that cities create and suggests for changes in housing, traffic, design, planning, etc. Although Jacobs writes that the most important part of her argument is the economic and social behavior of cities, it is clear that one of the most important factors to Jacobs is REAL LIFE. Jacobs writes in her introduction that unsuccessful city areas that do not have the mutual support economically and socially and “ that the science of city planning and the art of city design, in real life for real cities, must become the science and art of catalyzing and nourishing these close-grained working relationships.” It is the lack of urban planners and anyone else involved in the development of great cities observing how real cities function well and how real life functions with the cities that Jacobs calls out. Jacobs uses a brief example of a housing project’s grass in New York and how everyone hated the grass who lived there because it was an illusion that all was well with the housing project when it really wasn’t. When developers built the place they never asked the people who were going to live there what they wanted, again the lack of dealing with real life.

Jacobs then goes on to list people who have had the greatest impact on city planning theory such as Ebenezer Howard, Sir Patrick Geddes, the Decentrists (Lewis Mumford, Clarence Stein, Henry Wright, and Catherine Bauer) and Le Corbusier. Howard’s did not like cities and his ideas for them according to Jacobs were city destroying. Howards Garden City model that was also embraced by the Decentrists, was to thin cities out, de-center them, create smaller separate cities or even towns. Streets were bad, people should never be on them, commerce and residence areas should always be separate from each other, and the city should be self-contained and never change or grow. Jacobs claims that the Decentrists only looked at the failing parts of a city and nothing else, which left them with no understanding as to how a successful city would look and work. Although the Decentrists were against Le Corbusier, he also adopted some of Howards’s Garden City ideas in his Radiant City, a “vertical garden city.”

Le Corbusier’s vertical city was a city of towers with green all around and it embraced the unchangeable aspect of the Garden City plan. Le Corbusier felt that skyscrapers were the answer to the problems of cities. Many of these ideas became plans for low-income public housing. In many of the city of Chicago’s public housing developments, such as Cabrini Green, Robert Taylor Homes, Henry Horner Homes, and Harold Ickes Homes, the city embraced the high-rise building surrounded by green, and island off. All of these public housing plans have been deemed as failures that segregated low-income families off from the rest of the city, fostered gang activity, and created dangerous living environments. Today almost all are torn down and some are in the process of redevelopment in to smaller town homes with mixed income within the same space. The Garden City of the Decentrists and the Radiant City of Le Corbusier has had a great impact on the city of Chicago. Jacobs also claims that when she wrote the book in the 1950s city planners were combining the two plans to create cities and that this was a mistake.

In Jacobs’s chapter The Curse of Border Vacuums, she discusses how borders function in cities. Jacobs claims that massive single uses in cities create borders and those borders are damaging for neighborhoods in cities. Jacobs is concerned not with the social results of borders, but the physical and functional effects of borders on their direct surroundings. Things she lists as boarders are train tracks, waterfronts, big-city university campuses, civic centers, hospital grounds, and large parks. Since all of these types of boards she lists are not necessarily noisy unattractive, or undesirable of a location, there must be another reason that blight develops around these boards. Jacobs says that these boards form dead ends and walls for those who use city streets. She claims that for streets to stay safe there must be a constant mingling of people within these places for different reasons. The evidence Jacobs provides for this is an article published in the New York Post around the time she was writing the book, about a murder in an area that had become increasingly vacant once the construction of the Cross-Bronx Expressway began. Jacobs saw the construction of the Expressway creating lesson of a reason for people to go to that border causing fewer people to mingle in the area, causing shops to close early.

Jacobs divides all land in to two types general land and special land. General land is anywhere people circulate on foot in public, streets, small parks, and maybe building lobbies used like streets. Special land is not for public passage; people walk around it or next to it, it is technically in the way. A person circulating on foot in public is either not allowed in this special land or does not care to enter it, such as homes or places of work. Although special land contributes the people for general land, it also interferes with it. The evidence that Jacobs provides is a term used by downtown merchants “dead place” a place that goes empty on a downtown street. A dead place causes significant loss in foot traffic in the area around it because there is no use for it, and no reason for someone to go in to it or even go near it. This causes a “geographical obstacle to the general land.” Again, Jacobs shows when a border has only a single use than less people will come to it and mingle. Jacobs’s approach to correcting these single use borders is to create a seamless border. She suggests that parks should not put their activities such as ice-skating rinks in the center of the park but on the border. Then with corporation of the areas next to this border create something like a cafe or a place to rent skates in the area across from the border. This approach will allow for a seamless border that will help create multiple uses.

Robert Moses

In Robert Fishman’s Revolt of the Urbs the argument is that Moses’s critics of his plan to put a highway through Washington Square Park led to the larger debate on American Urbanism. One sees how Robert Moses convinced the public that he knew what was best for them, which was usually a massive clearing of any section of land that happened to be in his way for his great bridges, highways, expressways, and even parks. Moses forced relocation for numerous people who he saw as in the way of his projects. The battle to build a highway through New York’s Washington Square Park in the 1950s is where Moses met his greatest opposition, particularly that of Jane Jacobs. Moses wanted to build a highway through the park linking to his Lower Manhattan Expressway. This goes against everything Jacobs writes about in her chapter on boarders. According to Jacobs’s theory on borders, the highway would create more borders and fragment the park into single use pieces, which would diminish mingling of people in that area. The issues Jacobs and others bring up that were against Moses’s ideas were that diverse neighborhoods were at the heart of a city, pedestrians and mass transit should be focused on over the automobile, the importance of public space, and the “traditional streetscape” over skyscrapers in the park. Lastly, and probably the most important idea especially to Jacobs was listening to the people living in and using the city over the urban planner. This is where we come back to Jacobs’s argument that we need to observe “real life” to see how a city can function successfully, not just accepting the vision of the urban planner with the administrative power.

Extremely influenced by Le Corbusier’s ideas for the city of high towers with lots of room for automobiles on the ground, Moses embraced the automobile in the city. He rejected the small garden city town ideas of Mumford, but wanted to completely wipe out slum areas and rebuild a modern landscape. The House Act of 1949 not only secured government funding for many of Moses’s ideas, but also secured the support for clearing out the land he wanted to construct those ideas upon. It is clear that Moses’s unsuccessful attempt to fragment the park did not work, but he was responsible for many other projects that did just that through out the city of New York.

In Claes Oldenburg’s “The Street” and Urban Renewal in Greenwich Village, Joshua Shannon claims that Oldenburg relied on the “flames and wreckage” of New York’s Greenwich Village in the 1960s. He used this changing environment as his sort of canvas for his productions. The changing city was due to the modernist vision to create order within the city and to eliminate chaos. This meant getting rid of streets because that is where the chaos lies. The streets that photographer Helen Levitt photographed were the embodiment of this chaos with children using the streets as their playroom. In another of Oldenburg’s pieces, Snapshots of the City at the end of the performance he is hit by a cardboard car which is the final thing that finishes him off. This comment on the automobile is extremely appropriate for the time and the place. Oldenburg lived in the area around the Washington Square Park that had only just won its long battle of banning cars from the park.

Shannon points out the difference between Jane Jacobs’s view of the city and Oldenburg’s The Street was that Jacobs fought for a “delightfully quirky city” while The Street, portrayed it as dirty, violent, and full of poverty. The claim is that The Street’s image of the city is one of disorder or “of obdurate stuff refusing to be abstracted into order or legibility.” The point that Shannon is trying to make about Oldenburg’s work is that if he is trying to show an image of the city that is chaotic and disordered, he does not sell this image as a good one by depicting it as violent and dirty.

All of the readings this week discuss the ever-growing need by urban planners and city administrators to organize the chaos that in their eyes had taken over cities. Influenced from many different people from different countries what seems to be the biggest misconception by urban planners was their belief that one plan worked for all city problems and that this plan would be a permanent solution that would never need changing. This really leads me to agree with Jane Jacobs writing that there was a lack of observing real life in the city by urban planners and that without doing so they would never understand how a city could function well.

In The Death and Life of Great American Cities Jane Jacobs is not concerned with how a city “ought” to look, she is concerned with how it works. The brunt of her argument is that cities have intricate and diverse uses that give each other mutual support economically and socially. Jacobs breaks up her book in four parts, with the first part focusing on ordinary scenes and events, the social behavior of people in cities. The second part is her argument that economic behavior of cities is the most important factor. Part three is about decay and regeneration, how cities are used, how cities and the people in them behave in real life. The fourth part is about the problems that cities create and suggests for changes in housing, traffic, design, planning, etc. Although Jacobs writes that the most important part of her argument is the economic and social behavior of cities, it is clear that one of the most important factors to Jacobs is REAL LIFE. Jacobs writes in her introduction that unsuccessful city areas that do not have the mutual support economically and socially and “ that the science of city planning and the art of city design, in real life for real cities, must become the science and art of catalyzing and nourishing these close-grained working relationships.” It is the lack of urban planners and anyone else involved in the development of great cities observing how real cities function well and how real life functions with the cities that Jacobs calls out. Jacobs uses a brief example of a housing project’s grass in New York and how everyone hated the grass who lived there because it was an illusion that all was well with the housing project when it really wasn’t. When developers built the place they never asked the people who were going to live there what they wanted, again the lack of dealing with real life.

Jacobs then goes on to list people who have had the greatest impact on city planning theory such as Ebenezer Howard, Sir Patrick Geddes, the Decentrists (Lewis Mumford, Clarence Stein, Henry Wright, and Catherine Bauer) and Le Corbusier. Howard’s did not like cities and his ideas for them according to Jacobs were city destroying. Howards Garden City model that was also embraced by the Decentrists, was to thin cities out, de-center them, create smaller separate cities or even towns. Streets were bad, people should never be on them, commerce and residence areas should always be separate from each other, and the city should be self-contained and never change or grow. Jacobs claims that the Decentrists only looked at the failing parts of a city and nothing else, which left them with no understanding as to how a successful city would look and work. Although the Decentrists were against Le Corbusier, he also adopted some of Howards’s Garden City ideas in his Radiant City, a “vertical garden city.”

Le Corbusier’s vertical city was a city of towers with green all around and it embraced the unchangeable aspect of the Garden City plan. Le Corbusier felt that skyscrapers were the answer to the problems of cities. Many of these ideas became plans for low-income public housing. In many of the city of Chicago’s public housing developments, such as Cabrini Green, Robert Taylor Homes, Henry Horner Homes, and Harold Ickes Homes, the city embraced the high-rise building surrounded by green, and island off. All of these public housing plans have been deemed as failures that segregated low-income families off from the rest of the city, fostered gang activity, and created dangerous living environments. Today almost all are torn down and some are in the process of redevelopment in to smaller town homes with mixed income within the same space. The Garden City of the Decentrists and the Radiant City of Le Corbusier has had a great impact on the city of Chicago. Jacobs also claims that when she wrote the book in the 1950s city planners were combining the two plans to create cities and that this was a mistake.

In Jacobs’s chapter The Curse of Border Vacuums, she discusses how borders function in cities. Jacobs claims that massive single uses in cities create borders and those borders are damaging for neighborhoods in cities. Jacobs is concerned not with the social results of borders, but the physical and functional effects of borders on their direct surroundings. Things she lists as boarders are train tracks, waterfronts, big-city university campuses, civic centers, hospital grounds, and large parks. Since all of these types of boards she lists are not necessarily noisy unattractive, or undesirable of a location, there must be another reason that blight develops around these boards. Jacobs says that these boards form dead ends and walls for those who use city streets. She claims that for streets to stay safe there must be a constant mingling of people within these places for different reasons. The evidence Jacobs provides for this is an article published in the New York Post around the time she was writing the book, about a murder in an area that had become increasingly vacant once the construction of the Cross-Bronx Expressway began. Jacobs saw the construction of the Expressway creating lesson of a reason for people to go to that border causing fewer people to mingle in the area, causing shops to close early.

Jacobs divides all land in to two types general land and special land. General land is anywhere people circulate on foot in public, streets, small parks, and maybe building lobbies used like streets. Special land is not for public passage; people walk around it or next to it, it is technically in the way. A person circulating on foot in public is either not allowed in this special land or does not care to enter it, such as homes or places of work. Although special land contributes the people for general land, it also interferes with it. The evidence that Jacobs provides is a term used by downtown merchants “dead place” a place that goes empty on a downtown street. A dead place causes significant loss in foot traffic in the area around it because there is no use for it, and no reason for someone to go in to it or even go near it. This causes a “geographical obstacle to the general land.” Again, Jacobs shows when a border has only a single use than less people will come to it and mingle. Jacobs’s approach to correcting these single use borders is to create a seamless border. She suggests that parks should not put their activities such as ice-skating rinks in the center of the park but on the border. Then with corporation of the areas next to this border create something like a cafe or a place to rent skates in the area across from the border. This approach will allow for a seamless border that will help create multiple uses.

Robert Moses

In Robert Fishman’s Revolt of the Urbs the argument is that Moses’s critics of his plan to put a highway through Washington Square Park led to the larger debate on American Urbanism. One sees how Robert Moses convinced the public that he knew what was best for them, which was usually a massive clearing of any section of land that happened to be in his way for his great bridges, highways, expressways, and even parks. Moses forced relocation for numerous people who he saw as in the way of his projects. The battle to build a highway through New York’s Washington Square Park in the 1950s is where Moses met his greatest opposition, particularly that of Jane Jacobs. Moses wanted to build a highway through the park linking to his Lower Manhattan Expressway. This goes against everything Jacobs writes about in her chapter on boarders. According to Jacobs’s theory on borders, the highway would create more borders and fragment the park into single use pieces, which would diminish mingling of people in that area. The issues Jacobs and others bring up that were against Moses’s ideas were that diverse neighborhoods were at the heart of a city, pedestrians and mass transit should be focused on over the automobile, the importance of public space, and the “traditional streetscape” over skyscrapers in the park. Lastly, and probably the most important idea especially to Jacobs was listening to the people living in and using the city over the urban planner. This is where we come back to Jacobs’s argument that we need to observe “real life” to see how a city can function successfully, not just accepting the vision of the urban planner with the administrative power.

Extremely influenced by Le Corbusier’s ideas for the city of high towers with lots of room for automobiles on the ground, Moses embraced the automobile in the city. He rejected the small garden city town ideas of Mumford, but wanted to completely wipe out slum areas and rebuild a modern landscape. The House Act of 1949 not only secured government funding for many of Moses’s ideas, but also secured the support for clearing out the land he wanted to construct those ideas upon. It is clear that Moses’s unsuccessful attempt to fragment the park did not work, but he was responsible for many other projects that did just that through out the city of New York.

In Claes Oldenburg’s “The Street” and Urban Renewal in Greenwich Village, Joshua Shannon claims that Oldenburg relied on the “flames and wreckage” of New York’s Greenwich Village in the 1960s. He used this changing environment as his sort of canvas for his productions. The changing city was due to the modernist vision to create order within the city and to eliminate chaos. This meant getting rid of streets because that is where the chaos lies. The streets that photographer Helen Levitt photographed were the embodiment of this chaos with children using the streets as their playroom. In another of Oldenburg’s pieces, Snapshots of the City at the end of the performance he is hit by a cardboard car which is the final thing that finishes him off. This comment on the automobile is extremely appropriate for the time and the place. Oldenburg lived in the area around the Washington Square Park that had only just won its long battle of banning cars from the park.

Shannon points out the difference between Jane Jacobs’s view of the city and Oldenburg’s The Street was that Jacobs fought for a “delightfully quirky city” while The Street, portrayed it as dirty, violent, and full of poverty. The claim is that The Street’s image of the city is one of disorder or “of obdurate stuff refusing to be abstracted into order or legibility.” The point that Shannon is trying to make about Oldenburg’s work is that if he is trying to show an image of the city that is chaotic and disordered, he does not sell this image as a good one by depicting it as violent and dirty.

All of the readings this week discuss the ever-growing need by urban planners and city administrators to organize the chaos that in their eyes had taken over cities. Influenced from many different people from different countries what seems to be the biggest misconception by urban planners was their belief that one plan worked for all city problems and that this plan would be a permanent solution that would never need changing. This really leads me to agree with Jane Jacobs writing that there was a lack of observing real life in the city by urban planners and that without doing so they would never understand how a city could function well.